Advertisement

One family's escape from the Fall of Saigon for the U.S.

At daybreak on April 30, 1975, Van Le's father told his family it was time to go.

“Because I was a child, he said, ‘Oh, we’re just going on vacation,' ” Van said. “But apparently he told my siblings that we were gonna try to go to America.”

The Truong Le family — 7-year-old Van, his eight siblings, their father and their grandmother — had been living in Saigon through the final days of the Vietnam War.

Now, after decades of fighting, the communist forces of North Vietnam had encircled the city; the collapse of the U.S.-backed southern army was imminent.

For those with reason to fear the incoming regime, time was running out.

That morning, the family dressed more shabbily than usual — hoping to pass as rural farmers. Van's eldest sister thought to bring some family photographs. Their father stuffed a suitcase with cash, and stashed some documents in the glovebox of a Toyota station wagon. They took little else.

“There was not enough room for nine kids,” Van said. “So several siblings were riding a moped behind.”

The city was in chaos.

South Vietnam's fourth and final president, Gen. Duong Van Minh, had surrendered unconditionally, and social order broke down. Abruptly evacuated American homes now stood empty to looting, and people carted off whatever they could carry. Fearing retribution, South Vietnamese soldiers ditched their uniforms in the streets. Discarded guns, ammo and tanks littered roadways.

Van's father, Minh Thanh Le, had reason to flee. In the years before Saigon's fall, he had run afoul of the local communist guerrillas in their home province.

Targeted for their success

Born into a family of rural farmers in the 1930s, he'd shown an entrepreneurial spirit from a young age. By the time Van was born, in 1967, he owned multiple businesses, including lumber and sugar mills, and the biggest gas station in the province's eponymous capital, Tây Ninh.

“He was a big fish in that town,” Van said. “Tây Ninh is not a big town, but he was very well known, and my mother was very philanthropic. So they had a good thing going at that time.”

Their mother was well-educated, fashionable and worldly. When American dignitaries visited the province, she would regularly serve as interpreter.

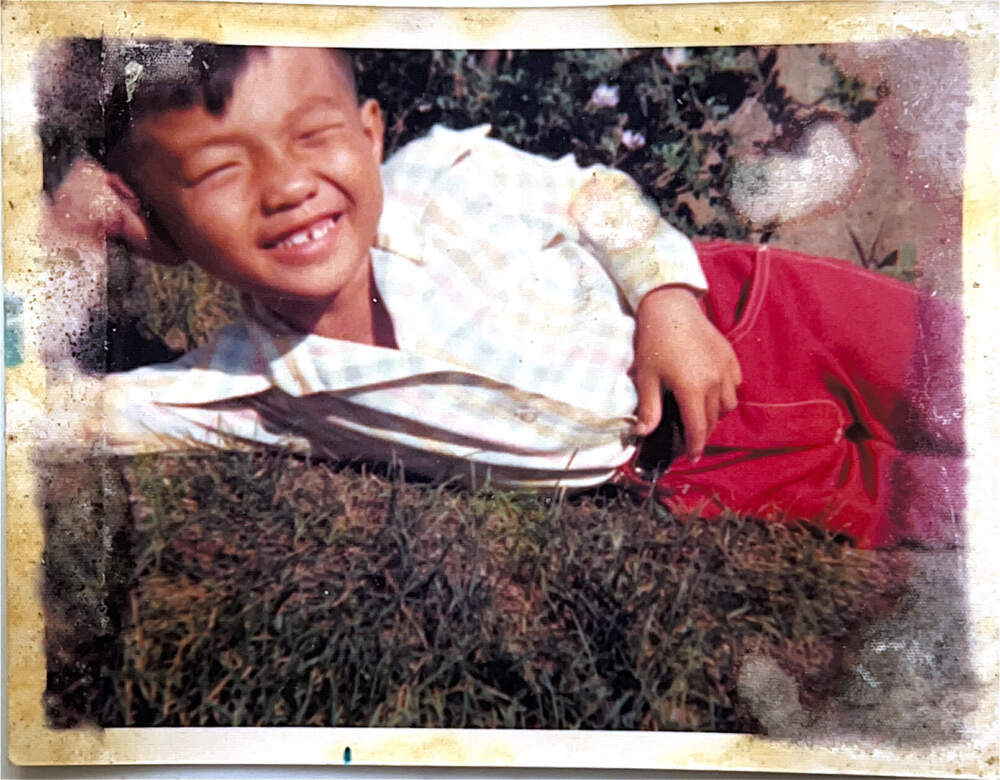

Van and his siblings remember an idyllic early childhood, growing up in a grand, French-built colonial home surrounded by gardens and groves of fruit trees. Their parents and beloved grandmother pushed them to excel in school.

The war — for the kids at least — felt far away.

An agricultural heartland populated mostly by peasants, Tây Ninh province was part of South Vietnam, but communist insurgents occupied significant chunks of the countryside. When they came calling on Minh Thanh Le, demanding he pay taxes on his industrial properties — land they claimed to have "liberated" to the communist cause — he refused to cooperate.

This led to death threats, and around 1970, a shooting attempt on his life. The sniper's bullet missed its target, but passed through their mother’s shoulder and lodged in little Van’s back.

Van fully recovered, thanks to quick work by an American doctor at the nearby U.S. Army base.

Their mother survived, but was never fully herself again. Her husband spared no expense — on one occasion flying her to Japan for treatment. She died in 1973 after a long battle with stomach cancer.

With the fighting around Tây Ninh intensifying, the family joined a flood of other refugees bound for Saigon, to ride out the final year of the war.

Advertisement

Getting out

Now, on April 30, 1975, they joined thousands of other families in a bid to escape Saigon — and Vietnam — entirely.

The options were slim. Some headed to the U.S. Embassy to join the throngs of people hoping to board an American helicopter — a privilege reserved for foreign nationals and those Vietnamese who could prove their loyalty to the United States. Others fled to boats in the Saigon River, only to find communist troops blocking their way to the sea.

So the Truong Le family decided to make a break for the coast instead — a 45-mile drive south from the city.

They drove slowly south toward the Saigon city limits on roads cluttered with the debris of war and echoes of sporadic sirens and gunfire. Frequent stops were made to let North Vietnamese troops and tanks pass in their victorious march toward the city center.

After the city came the road blocks, or checkpoints, where communist soldiers searched for deserters and those with U.S. sympathies.

The family presented themselves as farmers headed home to the countryside and feigned delight at the North's victory. But they were nervous: the documents their father had stashed in the glovebox — hidden in the leaves of a notebook — contained unsent letters to his own siblings, who had remained in Tây Ninh, detailing his business holdings and his true feelings about the communist regime.

At one checkpoint, their story clearly wasn't believed, and the soldiers ordered them out so they could ransack the car.

“If they had found [those papers], there’s no way we would have made it,” Van said.

"If they had found [those papers], there’s no way we would have made it."

Van Le

But one of the telltale giveaways — their father's diamond Rolex — became their salvation, when he quietly pressed the watch upon the guards. They were allowed to pass.

There was good reason to be nervous. As they were waved through the gated barricade to the road beyond, they passed another car not unlike their own, with a man and woman in the front and two children in the back — all shot dead.

“Oh my god, it was awful,” recalled Mary Truong, Van's elder sister. “I was 14 and for me, I, it's like a flashback whenever I think about it. ... [Like] a film, it rewinds it again.”

It took them more than 12 hours, but they finally made it to the Gò Công coast.

There, they abandoned the car and went looking for a boat.

Others had the same idea, and they soon fell in with an ad-hoc group, including other civilians, plus a group of fully armed deserters from the South Vietnamese Army.

When they'd identified the owner of one shabby, wooden tugboat, their father produced his suitcase stuffed with cash.

“Here, along with the soldiers, he made an offer the boat owner couldn't refuse, I guess,” Van said.

They spent about a week floating in the South China Sea before a U.S. Navy vessel came to their rescue. During that time, they endured gunfire and harassment from passing Vietnamese helicopters, and a shortage of food and water.

Their father had left all of his wealth — properties and possessions — behind in Vietnam.

The Truong Le family was among the nearly 130,000 refugees — most from Vietnam, some from Laos and Cambodia — who arrived in the U.S. during the spring and summer of 1975.

They were initially placed in a Pennsylvania refugee camp, near to where their late mother's physician, an American named John Lloyd, was from.

Dr. Lloyd soon connected them with a Catholic Church in Pittsburgh, which welcomed the family and gave them a place to live.

Van was now 8 years old.

“I thought it was just amazing,” Van said. “The houses were big, the streets were clean. There were no soldiers ... it was kind of like paradise.”

At first, the family lived on government assistance and the generosity of their sponsors and neighbors.

“It was a community effort,” Van recalled. “They donated furniture and food. They helped with rent, because my father didn’t have any money.”

In time, their father found a job as a janitor at the Frick Museum.

“He didn't want to be a charity case, so he insisted on working,” Van said. “He would take me to work sometimes, and I was sad to see that he was was mopping the floors. ... But he was perfectly happy to do it, because that's the unbreakable spirit that my father had.”

Over the next several years, Van would would live in many places with his father: Queens, New Orleans, Houston.

Until age 12, when it was decided Van would move to Boston to live with his older sisters and grandmother. The siblings' father remained in Houston to be with his new partner.

Van would go on to attend Boston Latin Academy, then the prestigious Commonwealth School, then Harvard College, and finally Northeastern Law School, where he graduated in 1996. Today, he has his own law practice in Boston.

His father, Minh Thanh Le, died in 2015 at around age 80.

Looking back, 50 years after the close of the Vietnam War, he says none of this would have been possible without the warm welcome his family received in the United States, and without the help of total strangers.

“The generosity and kindness of ordinary Americans helped to give us a new life,” he said. “So many of us Vietnamese immigrants and refugees are extraordinarily grateful for the opportunity, and the life, and the second chance we were given here.”

Today, Van lives in Quincy, as does his sister, Mary. Their seven other siblings live throughout the United States.

They are all American citizens.

This is part three in a series marking 50 years since the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War.

This segment aired on May 1, 2025.